- November/December 2025

- Volume 66

- Issue 7

How to Manage Stress Concentrations in Turbomachines

Key Takeaways

- Stress concentration arises from geometric discontinuities, leading to localized stress increases and potential failure through crack propagation.

- Stress concentration factors quantify stress increases, with ductile materials often yielding plastically, reducing immediate failure risk.

Among other causal factors, stress concentrations accumulate in areas with sharp edges, so filleting and chamfering is required to enable the smooth flow of stress streamlines.

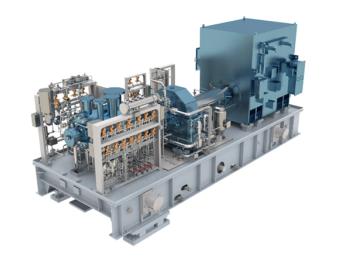

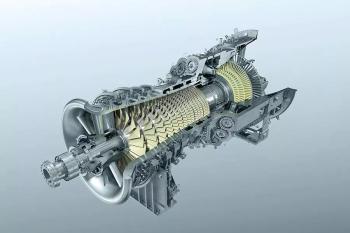

A stress concentration is a location in a turbomachine, component, or structure where stress risers are heavily accumulated. Equipment, components, parts, or items are stronger when force is evenly distributed over their areas, and any discontinuity or sharp change results in a localized increase in stress. Components and members usually have holes, grooves, notches, keyways, shoulders, threads, or other abrupt changes in geometry that create a disruption in the otherwise uniform stress pattern.

These aspects result in the possibility of stress concentration zones and areas for nearly any part of the turbomachine. Rotating shafts require shoulders, allowing the bearings to be properly seated and capable of taking thrust loads. The shafts should typically have machined key slots for securing rotating components. Other parts require holes, oil grooves, and notches of various kinds.

A part or component can fail via a propagating crack or other failure mechanism, specifically when a concentrated stress exceeds the material’s strength. The real fracture strength of a material is always lower than the theoretical value because most materials contain small cracks or contaminants (especially foreign particles) that concentrate stress. Fatigue cracks usually start at the stress concentration; therefore, removing such defects increases the fatigue strength.

Classic failure cases due to stress concentrations include metal fatigue or brittle fractures at the sharp corners—brittle fracturing in sharp corners has been reported in cold and stressful conditions. Attention is required for components and parts under high stresses, high-speed rotating equipment (such as high-speed rotor assemblies), high-pressure equipment, equipment fabricated with special materials, and units with high thickness and low-temperature operation.

GENERAL NOTES

Stress concentration accumulates in a system due to sudden changes in its geometry, loads, or material properties. When there is a sudden change in the body’s geometry due to cracks, sharp corners, holes, and decreases in the cross-section area, then there is an increase in the localized stress near regions. Geometric discontinuities cause a component or part to experience a local increase in the intensity of a stress field.

Loads and moments have been applied in limited geometries, and this can cause stress concentration. Concentrated loads result in large-scale stresses in the vicinity of the load application point. Discontinuities in the material itself, such as non-metallic inclusions in steels or variations in the strength and stiffness of the component elements, are additional sources of stress concentration.

STRESS CONCENTRATION FACTOR

Discontinuities in components, loads, or materials lead to local increases of stress, and this high stress can be expressed as a factor to the uniform stress in the component. The stress concentration factor is a dimensionless factor which is used to quantify how concentrated the stress is and is thus defined as a ratio of the highest stress in the element to the reference stress, which is usually the part’s uniform stress.

STRESS CONCENTRATION VS. DUCTILE BEHAVIOR

Stress concentration is often neglected when the material behaves in a ductile manner. This may be theoretically correct if all the conditions of pure ductile behavior are applicable. However, this is just theory and cannot be applicable in many practical cases such as those involving low temperatures, special geometries, imperfections, defects, etc. In other words, truly ductile materials are not as susceptible to stress concentration and associated rapid failures since they can yield plastically, deform at the points of localized stress, and not exhibit immediate failure. However, such a pure ductile behavior can be deviated due to many reasons.

In ductile materials, as the load increases, the localized concentrated stresses also increase at places subject to stress concentration. Here, the value of stress reaches the value of yield stress earlier than places surrounding or adjacent to these locations. After the stress concentration areas have reached yield stress, the localized zone would show plastic deformation behavior (or ductile behavior) rather than brittle fracture behavior (crack formations, etc). In the localized zone of stress concentration, the strain will increase at relatively constant stress rather than experience crack formation or other concerning failure mechanisms.

The key point is, in many cases, the ductile behavior can transform to detrimental brittle fracture behavior or other mechanisms, even without any warning. For instance, if a micro-void is located at the point of stress concentration, it would be the initiation site for a crack. It would propagate rapidly under continued stress and lead to premature failure. This is a major problem associated with stress concentration zones, so it is always required to properly investigate stresses and behavior in stress concentration areas.

The internal state of the material or metal, such as grain type and size, state of stress, stress gradient, temperature, and rate of straining may affect the stress experienced and stress concentration. All these factors may influence the ability of the material to make local adjustments in reducing the damaging effect.

SOLUTIONS & PRACTICAL NOTES

Often, a minor but thoughtful modification in the part’s shape can reduce the stress concentration considerably. For example, utilizing the largest possible radius when transitioning from one diameter to another will minimize the stress concentration. Sharp corners should be avoided.

A method used to decrease stress concentration is creating a fillet or chamfer at the sharp edge, as it enables the smooth flow of stress streamlines. By providing the fillet radius (or similar) at sharp corners or sharp changes, the cross-section area decreases gradually instead of suddenly, distributing the bodily stress more uniformly.

Amin Almasi is a Chartered Professional Engineer in Australia and the U.K. He is a senior consultant specializing in rotating equipment, condition monitoring, and reliability.

Articles in this issue

about 1 month ago

Myth: Axial Compressors are Better for High-Flow Applicationsabout 2 months ago

Recapping TPS 2025: Hydrogen Tech, New Gas Seals, and the Rise of Pumpsabout 2 months ago

Steam Turbine Optimization for Mechanical Drive Applications – Part 2about 2 months ago

Turbomachinery International: November/December 2025Newsletter

Power your knowledge with the latest in turbine technology, engineering advances, and energy solutions—subscribe to Turbomachinery International today.