- November/December 2025

- Volume 66

- Issue 7

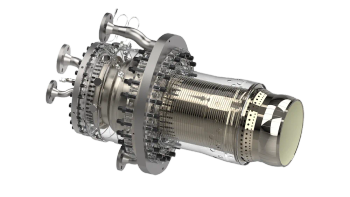

Myth: Axial Compressors are Better for High-Flow Applications

Key Takeaways

- Traditional charts for compressor selection are outdated, often leading to suboptimal choices between axial and centrifugal compressors.

- Axial compressors have limitations, including lower reliability, narrower operating ranges, and higher costs compared to centrifugal compressors.

Many turbomachinery diagrams are outdated and recommend axial machines over centrifugals, but modern technological advancements must be considered for industrial applications.

Allow me to rant about axial compressors. In our industry, we often rely on old engineering textbook charts to guide us on which type of compressor is best for a given application. We usually specify volume flow, pressure ratio, and/or discharge pressure (and sometimes impeller specific speed or head/flow coefficients) and then consult an old chart to assess whether the application requires an axial, centrifugal, reciprocating, screw, or diaphragm compressor.

These ancient charts, which can be found in all turbomachinery books (including mine), are part of the engineering canon and are considered unquestionable truth. This is especially the case when deciding between an axial or centrifugal machine. The generally accepted norm is that axials are good for high flows and lower pressure ratios, while centrifugals are pegged for low flow and high-pressure ratios—no further discussion allowed. To be clear, this rant is strictly about industrial applications for axial compressors, not the axial air compressors in gas turbines.

However, most of these diagrams were developed 50–70 years ago when turbomachinery technology was of a different age. High and mixed-flow centrifugal compressor impellers were not aerodynamically feasible, rotordynamic understanding was limited, diffuser designs were crude, stall and surge aerodynamics were a mystery, impeller blade passages were two-dimensional, disk and blade dynamics were estimated, return channels were straight, inlet/outlet vanes and nozzles were basically ducts, and Reynolds and Mach number corrections were inconsistent. With the advances in 3D computational fluid dynamics, finite element analysis, and other modern analysis and design techniques, as well as advanced manufacturing methods, the industry has been able to drastically extend the flow range of centrifugal compressors over the last 50 years.

Still, in many process applications where flow and head could be handled by centrifugal compressors, axial compressors are specified because of such outdated charts. In many cases where an axial compressor is selected, a larger-frame centrifugal or multiple centrifugals in parallel would provide a much more reliable, cost-efficient, and operationally superior solution. This is especially true when a wide operating range is required or if the pressure ratios are near what axials with a reasonable number of stages can achieve. As most axial compressors use horizontally split designs, there is also a much lower discharge pressure limit on axial compressors. Thus, due to their construction and design, axial compressors have inherent disadvantages in many process compression applications. Let's talk about this.

AXIAL SHORTCOMINGS

Axial compressors are inherently less reliable by their method of construction, with many blades fitted into a wheel. Individual airfoils must be long and thin to enable good efficiency, and they are usually freestanding, unlike industrial centrifugal machines with short blades that are usually shrouded. For these numerous, somewhat fragile components, construction quality can affect reliability and integrity.

These machines are not designed for rugged applications. They also have a much smaller flow operating range and significantly more aerodynamic and mechanical stability problems. A single blade failure usually leads to the complete catastrophic failure of downstream stages, known as “corn-cobbing.” Axials are also much more prone to aerodynamic instabilities such as rotating stall, flow separation, and flutter. Surge events in axial compressors are incredibly violent and often require immediate overhaul or repairs.

The flow operating range is much wider on centrifugal compressors than on axials. Centrifugals have relatively horizontal speed lines that provide a wide flow range on a single speed line, while axials have very steep speed lines that limit the operating range. Due to poor incidence angle matching at part speed, aggravated by the large number of stages, the speed range where an axial can operate is limited. That is why variable inlet guide vanes (VIGVs) are required for the first four to six stages to manage blade incidence angles at part speed and part load. However, VIGVs provide an inherent leakage path for process gas that is very difficult to perfectly seal. They also tend to seize if not properly lubricated and actuated frequently. A single misaligned VIGV can quickly lead to high-cycle fatigue failure due to the aerodynamic 1X excitation it causes.

Axials usually consist of many stacked wheels with individually mounted blades. These numerous parts and pieces can loosen, vibrate, and mechanically fail. Axial blades are typically thin and long, with many vibration modes that can be excited by aerodynamic instability and flutter. Long 15–20 stage machines have many blade and shaft resonances. In axials, multiple VIGV stages are mechanically linked, and they fail easily and frequently. If even one actuator link fails, the result is a 1X aerodynamic excitation that often leads to catastrophic high-cycle fatigue failures.

Surge control itself is challenging. In axial air compressors it can be managed with bleed, but in process gas applications a recycle loop back to suction is a challenging design due to complex piping requirements. Upstream uneven flows caused by piping elbows or bends have a significant impact on flow stability in axial compressors, much more so than in centrifugal compressors.

WHY CENTRIFUGALS?

The argument is often made that if you can squeeze the required flow into a single casing (axial compressor) versus two or three parallel centrifugal casings, the equipment will be cheaper. That is simply not true. A given pressure ratio may require 17-19 axial stages, but less than half that number of stages for a centrifugal compressor. It is true that for high-flow requirements, an axial compressor provides twice the flow of a centrifugal for the same frontal diameter. But a 17-19 stage axial process compressor is often two to three times the price of a centrifugal compressor with a similar pressure ratio, so a centrifugal solution may actually be cheaper in some cases.

To be clear, axial compressors can achieve higher flow rates than centrifugals, but state-of-the-art centrifugal compressors can capture high-flow applications that were considered exclusively for axial compressors in the past. The capability to operate at transonic conditions and very high flows has become essential, for example, in LNG applications, and is thus well established. Centrifugal compressors provide much higher head in smaller footprints, achieving higher energy density. If they are flow limited, one usually needs to select a larger casing. If flow cannot be handled in a single casing, multiple casings in parallel are an option, which also provides more operational control. Repair and overhaul costs of axial compressors are also much higher than those of centrifugal compressors, and their reliability tends to be lower.

Clearly, axial compressors have their place in industrial applications and have proven to be reliable and efficient in many contexts. But the traditionally accepted criteria defining where centrifugal versus axial compressors should be used is outdated, considering advances in centrifugal compressor capabilities. The operability range of centrifugal compressors has drastically increased with modern designs, and centrifugal compressors are clearly more reliable, rugged, and operationally flexible than axial machines. Rather than relying on old charts to decide which type of machine to use in a process, one should review and analyze the required operating characteristics and then perform a fair and rational one-on-one comparison. This will often yield surprising results.

Klaus Brun is the Vice President of Product & Technology at Ebara Elliott Energy. He is also the past Chair of the Board of Directors of the ASME International Gas Turbine Institute and the IGTI Oil & Gas Applications Committee.

Rainer Kurz is a recent retiree as Manager of Gas Compressor Engineering at Solar Turbines Inc. in San Diego, CA. He is an ASME Fellow and has published over 200 articles and papers in the turbomachinery field.

Articles in this issue

about 2 months ago

How to Manage Stress Concentrations in Turbomachinesabout 2 months ago

Recapping TPS 2025: Hydrogen Tech, New Gas Seals, and the Rise of Pumpsabout 2 months ago

Steam Turbine Optimization for Mechanical Drive Applications – Part 2Newsletter

Power your knowledge with the latest in turbine technology, engineering advances, and energy solutions—subscribe to Turbomachinery International today.